The Gratitude Prescription: Lessons from Steve Jobs and Everyday Life

by Barry Brownstein

We can choose to invest our love either in our controlling, self-centered mind or in the part of ourselves that connects to something greater than we can fully understand.

Is it just the long lines that make trips to the post office or DMV so unpleasant? The reality goes deeper. In many states, a significant number of government employees act as though they’re doing you a favor by helping you.

These workers seem to find no meaning in their work, and they stubbornly refuse to allow any joy into their workday.

Passion for our work develops from our commitment to being good at our job. Those who would rather be idle because they feel no passion are deluded about cause and effect.

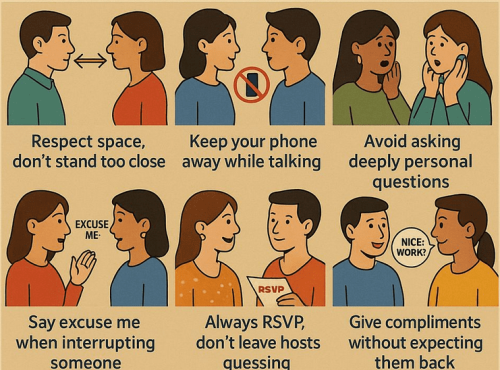

In contrast to experiences at government offices, market transactions are shaped by mutual benefit—each participant values what they receive more than what they give. This interdependence naturally fosters a sense of gratitude.

Even the briefest interactions can be transformed by a genuine smile or a few kind words, acknowledging the humanity we share. Last summer, while on vacation, my wife and I frequented a busy ice cream shop staffed by two Bulgarian guest workers, with whom we exchanged pleasantries. They shared their plans to marry when they returned home. Although they may not return to the United States for several years, if our paths cross again, we’ll greet each other warmly, as friends.

Psychologist David K. Reynolds teaches that gratitude is a natural response to keeping our eyes open as we operate in the world.” Reynolds is referring to the way others support our lives—from our bountiful food supply, to running water, to modern technology. We would quickly perish without the efforts of untold people, present and past. Reynolds pointedly says, “It takes a certain amount of effortful blindness to miss [this] truth about what the energy of others has provided for us.”

Reynolds observed, “I’ve never met a suffering neurotic person who was filled with gratitude.” We can test this proposition for ourselves. When we are most caught up listening to the noisy, chatterbox voice in our heads, how do we feel? How much gratitude do we feel for others and our lives? To ask those questions is to answer them.

Yet, a resolve to feel more grateful can fall short. Reynolds observes, “Gratitude is a feeling, and so is uncontrollable directly by our will. We cannot generate gratitude simply by telling ourselves to be grateful.”

Gratitude is fostered through our growth in moral and spiritual understanding, as well as through our exploration of the economic principles that help humanity flourish.

Our moral growth may reveal that we are not isolated beings struggling to survive in a dog-eat-dog, win-lose world. Instead, we are connected to a Source that brings goodness, creativity, and love into our lives. These gifts are inherently ours, and gratitude naturally arises from recognizing what we receive through grace.

Reynolds has advice for living: “It isn’t enough to feel gratitude; it is important to do something constructive, purposeful… Being mature and psychologically healthy doesn’t mean feeling good all the time. Maturity means acting responsibly, positively, whether we feel good or not, grateful or not.” Perhaps you have observed, as I have, that the mentally healthy among us seem to follow that advice.

Read more about David Reynolds and his ideas on Constructive Living in our Mindset Shifts U archives.

Steve Jobs, in his famous 2005 Stanford commencement address, shared the importance of doing something meaningful each day. Jobs began: “When I was 17, I read a quote that went something like: ‘If you live each day as if it was your last, someday you’ll most certainly be right.’” He continued,

It made an impression on me, and since then, for the past 33 years, I have looked in the mirror every morning and asked myself: “If today were the last day of my life, would I want to do what I am about to do today?” And whenever the answer has been “No” for too many days in a row, I know I need to change something.

In 1983, speaking at a conference of Apple designers, Steve Jobs pointed out the importance of their work. He presciently forecasted that “By ’86, ’87, pick a year, people are going to spend more time interacting with these machines than they do interacting with automobiles today.”

That story and more are contained in Make Something Wonderful, an evocative compilation of Jobs’s writings, speeches, and interviews.

Reading Make Something Wonderful, it’s clear Jobs never thought of himself as a lone great mastermind. If something revolutionary was going to happen, it would be because ordinary people imbued with a willingness to work towards an extraordinary goal were free to create by their voluntary cooperation. A controlling mastermind can be as much of a barrier to business success as a government planner.

Responding to a question at that 1983 design conference, Jobs told his audience they were “in the right place at the right time to put something back.” Jobs explained why the opportunity to “put something back” is enlivening: “Most of us didn’t make the clothes we’re wearing, and we didn’t cook or grow the food that we eat, and we’re speaking a language that was developed by other people, and we use a mathematics that was developed by other people. We are constantly taking.”

Jobs continued, “And the ability to put something back into the pool of human experience is extremely neat…And we [will] look back— and while we’re doing it, it’s pretty fun, too— we will look back and say, ‘God, we were a part of that!’”

As you read the following goal Jobs shared with the designers, remember this is 1983:

What we want to do is put an incredibly great computer in a book that you carry around with you, that you can learn how to use in twenty minutes. That’s what we want to do. And we want to do it this decade. And we really want to do it with a radio link in it so you don’t have to hook up to anything— you’re in communication with all these larger databases and other computers. We don’t know how to do that now. It’s impossible technically.

Fast forward to 2010. Jobs’ dream has come true in a way no one could have imagined. In just over a year, Jobs would die. Despite his failing body, Jobs was still thinking about giving and receiving. From his iPad, he sent himself this email:

I grow little of the food I eat, and of the little I do grow I did not breed or perfect the seeds.

I do not make any of my own clothing.

I speak a language I did not invent or refine.

I did not discover the mathematics I use.

I am protected by freedoms and laws I did not conceive of or legislate, and do not enforce or adjudicate.

I am moved by music I did not create myself.

When I needed medical attention, I was helpless to help myself survive.

I did not invent the transistor, the microprocessor, object oriented programming, or most of the technology I work with.

I love and admire my species, living and dead, and am totally dependent on them for my life and well being.

Even someone like Jobs, who contributed so much to the world, recognized that he still received more from others than he could give back. Notice, too, that Jobs understood that the social order of this country protected his freedom to try to do what seemed impossible.

Like Marcus Aurelius, Jobs’s daily practice was to temper any arrogance with a good dose of his real place in the world. In his Meditations, Marcus reminded himself: “Take time to meditate on the interdependency of everything in the universe. How all things embrace one another, as if they were dear friends. How they defer to one another and form a sweet accord in obedience to the laws of nature.”

When Jobs shared, “You’ve got to choose what you put your love into really carefully,” he was referring to being overextended in business, but the advice is equally valid as we live our daily lives. Many great teachers all pointed to the impossibility of serving two masters.

We can choose to invest our love either in our controlling, self-centered mind or in the part of ourselves that connects to something greater than we can fully understand.

While we may not impact billions as Jobs did, nurturing gratitude within ourselves encourages us to give back in our own unique way, helping to create a world where others can more freely thrive.

Source: https://mindsetshifts.substack.com/p/the-gratitude-prescription-lessons

This essay was originally published at the Advocates for Self-Government.